Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [32] | next >> | Current column |

4874. ‘Chess expert aged four’

The following report was published on page 115 of CHESS, 1 January 1964 under the title ‘Chess expert aged four’:

‘A four-year-old Georgian boy, Zurab Sopia, is beating many grown-ups at chess, the newspaper Leninskoye Znamya has reported. The former world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik has visited him at his home near Sukhumi to help him polish his game still further.’

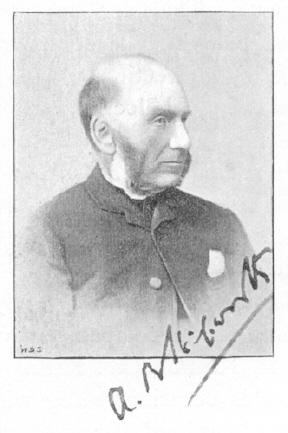

4875. Alain C. White

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

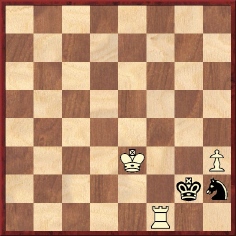

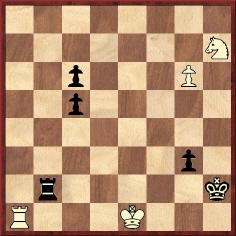

‘On the subject of prodigies, details of A.C. White’s early composing career were provided in Memories of My Chessboard (Stroud, 1909). He gave his first published problem, composed at the age of 11 and published in the Dubuque Chess Journal, December 1891:

Mate in twoWhite wrote (page 9):

“My father, the late Mr John Jay White, was a keen and thorough solver – and my ideas of chess strategy were picked up over the back of his chair. Thus I learned to solve problems with some facility early in 1891, at the age of 11. From the start I wanted also to compose, but I kept this ambition concealed until one day I was able to bring my father this first fruit of mine. At first he was quite incredulous, but on finding the position sound he was greatly pleased, I think, and in turn surprised me by having it published in ‘Old Brownson’s’ Magazine and one morning showing me my name in print over a splendid full page diagram. I had carefully chosen a theme for the problem (for my taste appears to have naturally inclined towards definite themes), namely the uncovery of four pieces by the white pawn, and I was proud of what I thought to be a real discovery till I learnt of Shinkman’s two-er on the same idea: see No. 12a.”

The problem referred to was by W.A. Shinkman in the Illustrated American, 1891:

Alain Campbell White

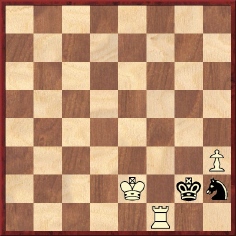

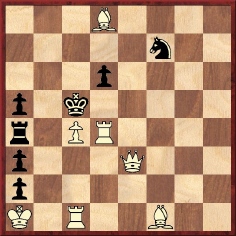

No. 3 in the book is from the Dubuque Chess Journal, 1892 (amended) and has an amusing story attached.

Self-mate in six

1 Rh1 R moves

2 White xR R moves

3 White x R P moves

4 BxP P moves

5 BxP P moves

6 BxP b2 mate.

White wrote (page 13):

“I entered No. 3 in one of his [Brownson’s] tourneys, which were often as erratic as he was himself. It was unsound in one line of play, but I have since patched it up. The idea of capturing Black’s men, until he is forced to give mate, is absolutely elementary. What delighted Brownson was the fact that if each combination was written out, severally, it would take some 5,000 lines to give a full solution. As points were offered for each variation in the problems he published, this gave promise of no end of fun. Even now when I mention casually that when 12 years old I composed a problem with 5,000 lines of play, I see a look of surprise on the faces of my listeners, who at best credit me with a vivid imagination.”

Given that White knew Sam Loyd from about 1890 (see Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems, page 105) I wonder whether his self-mate was inspired by Loyd’s four-mover on page 226 of the same book.’

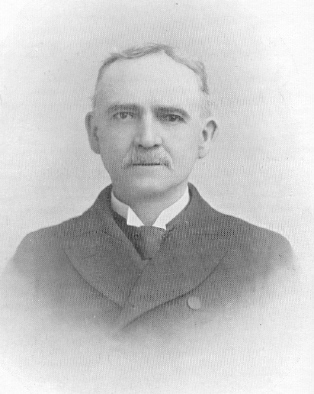

4876. Who? (C.N. 4870)

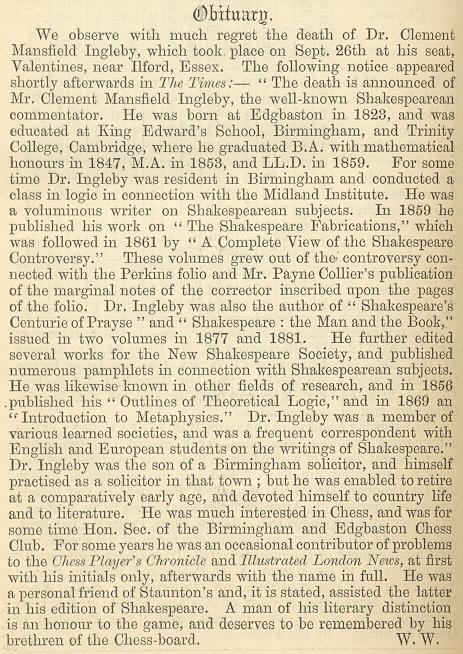

C.N. 4870 invited readers to identify the person whose obituary stated that ‘a man of his literary distinction is an honour to the game’ – a nineteenth-century figure who died in his sixties and was known not only for his activity in the chess world (e.g. the Chess Player’s Chronicle and the Illustrated London News) but also for his writings on Shakespeare as from circa 1860.

It was not Howard Staunton (1810-1874) but Clement Mansfield Ingleby (1823-1886). Below is the complete obituary published on page 416 of the November 1886 BCM:

4877. Tarrasch quote (C.N. 4868)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) points out that the following appeared on page 206 of Tarrasch’s Dreihundert Schachpartien (Leipzig, 1895), regarding his poor performance at the Leipzig, 1888 tournament:

‘Ich glaubte, es genüge vollkommen, mich ans Brett zu setzen und Züge zu machen, um zu gewinnen …

… Ich sah ein, daß es nicht genügt, ein guter Spieler zu sein, sondern daß man gut spielen muß.’

Our translation:

‘I believed that to win it was quite sufficient for me to sit down at the board and make moves …

… I recognized that it is not enough to be a good player, but that one must play well.’

In the 1909 and 1925 editions of Dreihundert Schachpartien the passage is on pages 189 and 190 respectively.

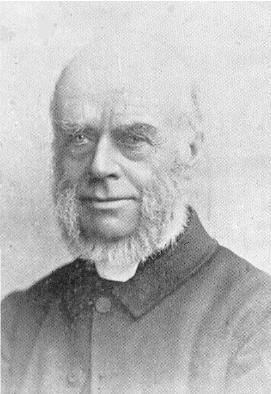

4878. Evans the doffer

Two major articles seem to include most of what is known about William Davies Evans (1790-1872) and the invention of the Evans Gambit: ‘Entwicklung des Evansgambits’ by M. Lange in the Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1873, pages 1-13, and ‘Captain Evans’ by W.R. Thomas in the BCM, January 1928, pages 6-18.

Max Lange’s article was accompanied by this picture of Evans:

A slightly different illustration was included in W.R. Thomas’s article (on page 7):

On page 18 Thomas wrote:

‘The article [by Max Lange] contains a good portrait of Evans. The only other one known to the writer is a faded photograph in the album of the Liverpool Chess Club. It represents an old man in a black skull cap, with a flowing white beard.’

In a follow-up letter on pages 84-85 of the February 1928 BCM Thomas wrote:

‘Mr [John] Keeble further informs me that he possesses another portrait of Evans. In 1871 H.F.L. Meyer issued a chess board picture, every square of which has a portrait. The players are in alphabetical order, Abbott at QR8, Wyvill at KR1. Evans is on QKt6, Lewis on QKt4: the Captain’s ghost must be restless.’

The full chess board picture was reproduced in C.N. 3467, and a detail of Evans is given below:

William Rowland Thomas was the father of A.R.B. Thomas (BCM, November 1919, page 370, and April 1936, page 159). His article referred to the exact burial place of Evans, in Ostend; see also page 258 of the June 1927 Chess Amateur, page 103 of the March 1990 BCM and page 25 of the booklet Schaakgraven (C.N. 4452). One other point in W.R. Thomas’s article requires further scrutiny, for on page 18 he stated:

‘Evans’ widow, Marie Thérèse Duncan Evans, survived him for three years, residing at Southborough. She was awarded a pension of £50 a year. Nothing is known of his son, nor are any descendants believed to be alive.’

However, Evans’ widow was still alive much longer after his death. Pages 97-98 of the December 1879 Chess Monthly carried an appeal on her behalf by Cyril Parkinson. Her age was given as 78, and she was said to be struggling against poverty in a cottage in Kent. Reference was also made to a ‘little grandson’. Page 325 of the July 1880 Chess Monthly published a letter from her (Mary Theresa Evans of 1 Oakfield Villas, Southborough, Tunbridge Wells) to the treasurer of the fund in which she expressed thanks for the aid received (over £50).

Finally, we add the following quote from an article entitled ‘Experiences of an Amateur’ on pages 163-164 of the May 1883 BCM:

‘On one occasion when I had just commenced a game at the Divan I observed an elderly gentleman suddenly raise his hat from his head and put it on again. He did this in a way to excite my curiosity, and on my venturing to ask him why he had done so he replied, “I am Capt. Evans, and whenever I see anyone playing my gambit I always acknowledge the compliment by taking off my hat”.’

The ‘Amateur’ did not identify himself but provided some pointers, stating, for example, that he had begun chess at school some 46 years previously, studied at Oxford (where he was a Blue) and belonged briefly to the St George’s Chess Club. He also referred to his chess activity in Leamington and Norwich and mentioned that he was well acquainted with the problem composer Horatio Bolton.

4879. Census information

In C.N. 4756 Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) provided from British censuses extensive information about Blackburne, Gunsberg, Hoffer and Steinitz. He now gives details regarding Gossip, Loman, MacDonnell (spelt Macdonnell), Mortimer, Ranken and Skipworth.

George Hatfeild Dingley Gossip:

1871 census: George Gossip, age 29. Born in New York (British subject). Address: 8 Mayfield Road (Hackney), London. Occupation: translator of languages. Married with Alicia Gossip (age 30, born in Dublin). Child: George Gossip (son, age 11 months). Other household members: Charlotte Pripke[?] (age 16), general servant; Lucy Pripke[?] (age 12), nursemaid.

1881 census: George H.D. Gossip, age 39. Born in New York, United States. Address: 1 Lilian Villas, Spring Road (St Helen), Ipswich. Occupation: author of work on chess. Married with Alice Gossip (age 40, born in Dublin). Children: Helen J. Gossip (daughter, age 9), Harold K. Gossip (son, age 7), Mabel M. Gossip (daughter, age 2).

1891 census: G.H.D. Gossip, age 49. Born in New York as a British subject. Address: 20 Alfred Place (St Giles), London. Occupation: literary profession. Widower. Gossip, a lodger, shared the address with: William Belcker[?] (age 49), lodger and assistant brewer; Gustav Dürholdt (age 24), lodger and electric engineer; W. Edmund James Leach (age 32), lodger and captain in army; Alexander Mackintosh (age 54), commercial traveller; Janet [surname illegible] (age 53), head and lodging house keeper; Lizzy Chapman (age 19), general servant (domestic).

Rudolf Johannes Loman:

1891 census: Rudolph [sic] J. Loman, age 29. Born in Amsterdam, Holland. Address: 49 Deronda Road (Lambeth), London. Occupation: teacher of music. Married with Hillegonda Loman (age 28, born in Groningen, Holland). Child: Rudolph Loman (son, age 2). Other household members: Eliya Thurston (age 21), general servant (domestic).

George Alcock MacDonnell:

1891 census: George A. Macdonnell, age 60. Born in Ireland. Address: The Vicarage, Bisbrooke. Occupation: vicar of Bisbrooke. Married with Jane Williams (age 61, born in Bisbrooke, Rutland). Child: Charles Macdonnell (son, age 38), agricultural labourer.

James Mortimer:

1881 census: James Mortimer, age 47. Born in United States. Address: 39 Pembridge Villas (Kensington), London. Occupation: editor of London Figaro. Married with Lydia Mortimer (age 25, born in London). Children: L.M. Mortimer (daughter, age 6), Minnie E. Mortimer (daughter, age 4). Other household members: Kate Witney (age 16), servant (domestic); L. Witney (age 19), servant (domestic).

1891 census: James H. Mortimer, age 57. Born in United States of America. Address: 162 Regents Park Road (St Pancras), London. Occupation: author, dramatist and journalist. Married with Lydia Mortimer (age 34, born in London), act dramatic artist. Children: Lilian M. Mortimer (daughter, age 16), Minnie E. Mortimer (daughter, age 14). Other household members: Maria Stevens (age 16), general servant (domestic).

Charles Edward Ranken:

1861 census: Charles E. Ranken, age 33. Born in Somerset Brislington. Address: 6 Trinity Terrace, Cheltenham. Occupation: Curate of Trinity Church, Cheltenham. Unmarried. Ranken, a lodger, shared the address with Giles Stephens (age 54), head and lodging house keeper; Mary Stephens (age 60), wife; Alice Stephens (age 37), sister and servant; Martha Dodwell (age 14), general servant; Marion Loch (age 61), lodger and fundholder; Thomas Ranken (age 21), visitor and scholar Cambridge.

1871 census: Charles E. Ranken, age 43. Address: Malvern Wells, Hanley Castle. Occupation: Curate in charge of Malvern Wells. Married. Ranken, a lodger, shared the address with Cecil Wakefield (age 41), head and chemist; William Bladen (age 22), assistant chemist; Mary Stuart (age 24), housemaid; William Fowler (age 17), errand boy; George Wilch [?] (age 15), errand boy.

1881 census: Charles E. Ranken, age 53. Born in Somerset Brislington. Address: Priory Road, Great Malvern. Occupation: Without Cure of Souls. Married with Louisa J. Ranken (age 39, born in Pendleton). Children: Francis A.J. Ranken (daughter, age 10), Emily F. Ranken (daughter, age 5), Herbert E. Ranken (son, age 3). One visitor was member of the household: Anne Fisher (age 44). Other household members: Sarah Harris (age 25), parlour maid domestic, Annie E. Highton (age 19), nurse maid domestic; Susan G. Hunt (age 14), nurse maid domestic; Elizabeth Stanton (age 23), servant.

Arthur Bolland Skipworth:

1861 census: Arthur B. Skipworth, age 30. Born in Laceby, Lincolnshire. Address: Priory, illegible [township near Stokesley]. Occupation: Perpetual Curate. Married. Child: George P. Skipworth (son, age 7 months). Other household members: Thomas Apcey (age 50), servant; Martha Apcey (age 51), servant; Harry Apcey (age 13), scholar; Emma Sharp (age 17), nurse maid.

1881 census: Arthur B. Skipworth, age 50. Born in Laceby, Lincoln. Address: Glebe House, Tetford. Occupation: rector of Tetford & Farming 291 Ac Land Under Lane. Employ 8 men, 1 woman & 2 boys. Married. Other household members: Mary Audiss [?] (age 71), housekeeper; William Parish (age 18), farm servant indoors; David Porters (age 21), farm servant indoors; James Wilkinson (age 28), farm servant indoors.

1891 census: Arthur B. Skipworth, age 60. Born in Laceby, Lincolnshire. Address: Holbeck Hall, Ashby Puerorum. Occupation: clerk in holy orders (rector of Tetford) & Farmer. Married. Other household members: Percy H. Robbs (age 17), boarder and farm pupil; Francis Bennett (age 52), farm bailiff; Sarah H. Bennett (age 42), housekeeper; Francis H. Bennett (age 19), lodger and auctioneers clerk; Eva Harrison (age 19), general servant (domestic).

4880. Alekhine in 1937

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) submits a photograph of Alekhine with his wife after the 1937 world championship match against Euwe. It comes from an unidentified Dutch publication.

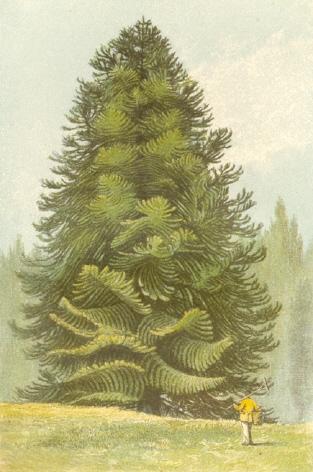

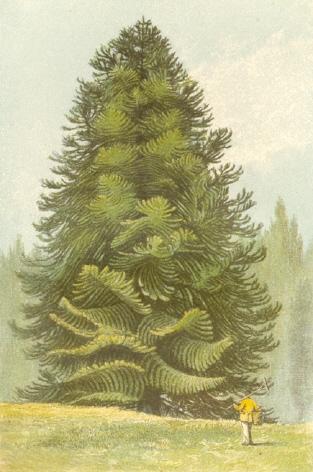

4881. Araucaria imbricata

This illustration was the frontispiece to a (non-chess) book by a familiar chess figure. Who?

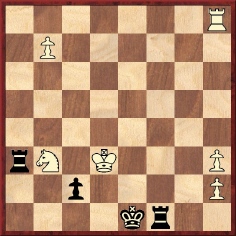

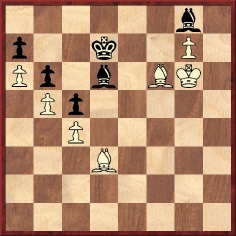

4882. Bishop ending

Our Royal Walkabouts article gave, from page 168 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 August 1884, the ending of a game between H. Colborne and Frederick William Womersley, Hastings, 1883 or 1884. Subsequently, Womersley adapted it into an endgame puzzle, reversing the colours and offering a book prize for the first solution (BCM, June 1886, page 264). A corrected position (with the black king on d7 and not e8) appeared on page 301 of the July 1886 issue, and the solution followed on pages 337-339 of the August-September 1886 BCM – over 80 lines of analysis.

White to move and win

4883. Gossip (C.N. 4879)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) has taken a photograph of G.H.D. Gossip’s house in that town (C.N. 4879):

4884. Spot the chessmaster (C.N. 4873)

Standing in the middle is George Thomas, the photograph having been taken at ‘the first-ever badminton international – Ireland versus England, Dublin 1903’. It was published on page 39 of The Badminton Story by Bernard Adams (London, 1980).

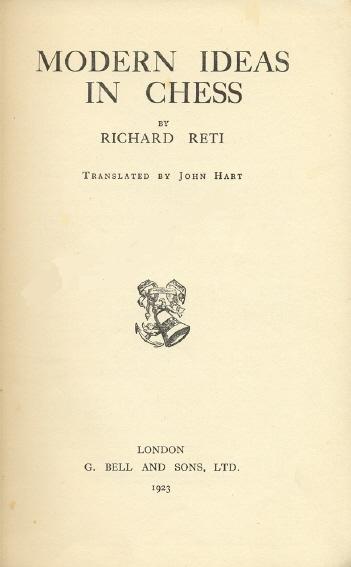

4885. John Hart

Andrew Templeton (Newmarket, Ontario, Canada) is seeking biographical information about John Hart, who translated into English Richard Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess (London, 1923). In particular, when did he die?

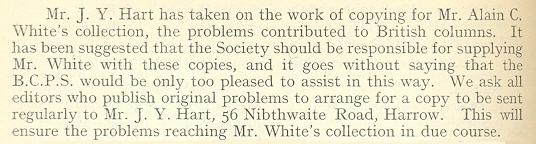

Readers’ assistance is requested. Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia has an entry for John Yealand Hart, who was born in London in 1884, and a reference to this item on page 418 of the October 1922BCM:

Was J.Y. Hart of 56 Nibthwaite Road, Harrow the translator of Réti’s book?

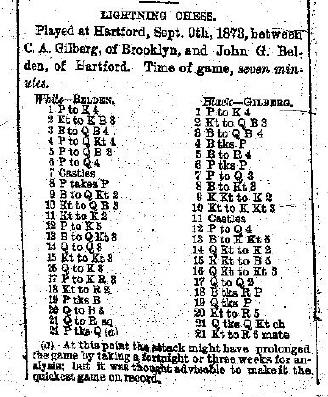

4886. Lightning chess

Courtesy of Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) an early citation of ‘lightning chess’ has been added to our feature article on Earliest Occurrences of Chess Terms, from the Hartford Times of 11 October 1873:

In this encounter between Belden and Gilberg, described as ‘the quickest game on record’, the likely move-order seems to us 17…Bxh3 18 gxh3 Qd7 19 Nh2, but below is the score as given in the newspaper:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O d6 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Bb2 Nge7 10 Nc3 Ng6 11 Ne2 O-O 12 e5 d5 13 Bb3 Bg4 14 Qd3 Nce7 15 Ng3 Nf4 16 Qe3 Neg6 17 h3 Qd7 18 Nh2 Bxh3 19 gxh3 Qxh3 20 Qf3 Nh4 21 Qh1 Qxg3+ 22 fxg3 Nh3 mate.

4887. Various spellings

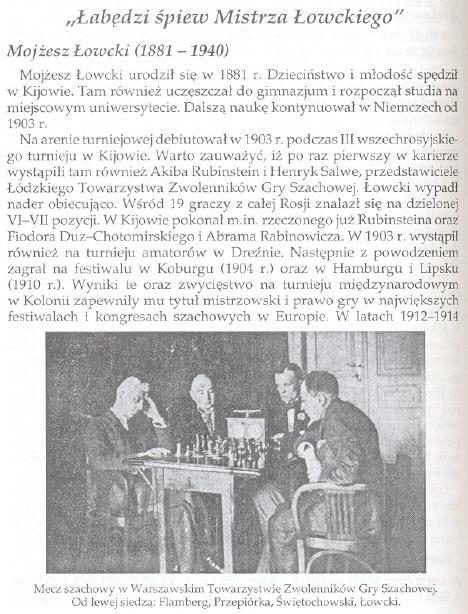

Noting such spellings as Lowcki, Lowcky and Lowtzky, Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks how that player’s name should be written.

Polish sources usually have Mojżesz Łowcki, i.e. with a kropka on the Z (dot accent) and a kreska ukośna on the L (barred L). Below is an extract from page 64 of volume two of Arcymistrzowie, mistrzowie, amatorzy by Tadeusz Wolsza (Warsaw, 1996):

Lowtzky is a version commonly seen in non-Polish sources, but further information on the relative ‘acceptability’ of such other spellings will be welcome.

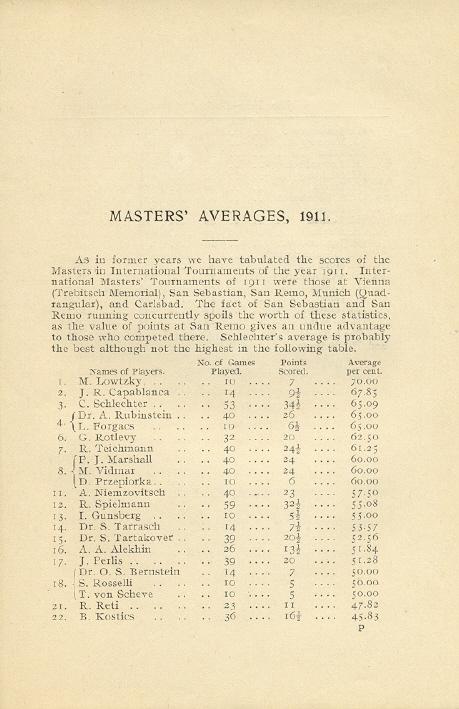

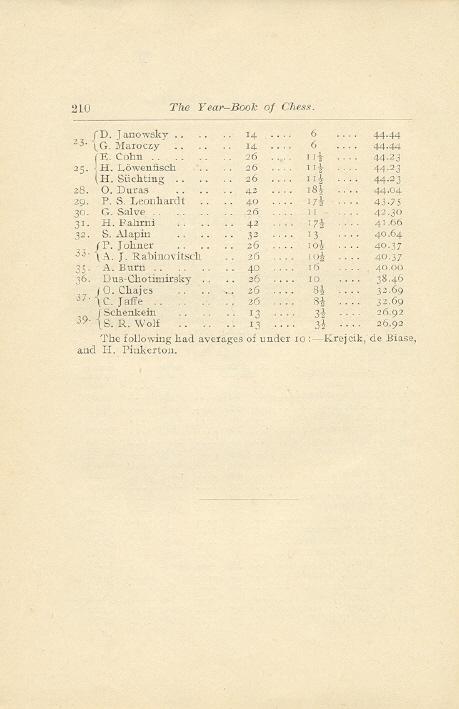

On the strength of his score at San Remo, 1911 Łowcki finished top of a list of ‘Masters’ Averages, 1911’ on pages 209-210 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1912 by E.A. Michell (London, 1912):

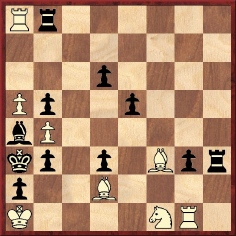

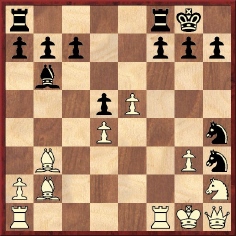

4888. Find the win

White to play and win.

At first glance it may appear that White can win at once with any of the following:

- 1 Qxh7+ Kxh7 2 Rh3+ Kg6 3 Ne7 mate

- 1 Ne7+ Kh8 2 Qxh7+ Kxh7 3 Rh3 mate

- 1 Nf6+ gxf6 2 gxf6+ Kh8 3 Qxh7+ Kxh7 4 Rh3 mate.

However, all these standard mating combinations are impossible because of the pin on the a8-hl diagonal, and the winning course is therefore the prosaic 1 Ne7+ and 2 Qxb7.

The position was discussed in C.N.s 741 and 796 (see page 1 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves), being taken from an article on chess blindness by Josef Krejcik on page 14 of the March 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung. Krejcik stated that the position had occurred in a game played by him, as White, against a well-known grandmaster in 1907, and he gave more or less the same text on pages 16-17 of his book 13 Kinder Caïssens (Vienna, 1924).

Here, though, we add a complication. On pages 189-191 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion (New York, 1956) Fred Reinfeld discussed a similar position:

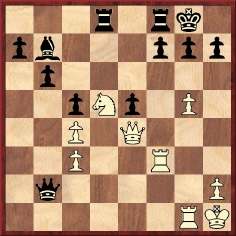

Reinfeld stated that this position arose in ‘a game played by two Viennese amateurs many years ago’ and that Maróczy was a spectator. White could win a pawn with 1 Nxc3 bxc3 2 Qxb7 Rxb7 3 Rxc3 but, Reinfeld said, would have difficulty in winning and therefore had the idea 1 Ne7+ Kh8 2 Qxh7+ Kxh7 3 Rh3 mate. Then White realized that the rook was pinned, but at this point Maróczy exclaimed ‘Magnificent’. Consequently, White looked for a finesse and found 3 d5 Qc8 4 Rd4 g6 5 Bf6 g5 6 Rdd3 g4 7 Rd4 Ne4 8 Rxe4 Qf5 9 Rh3+ gxh3 10 Rh4+ Qh5 11 Rxh5 mate.

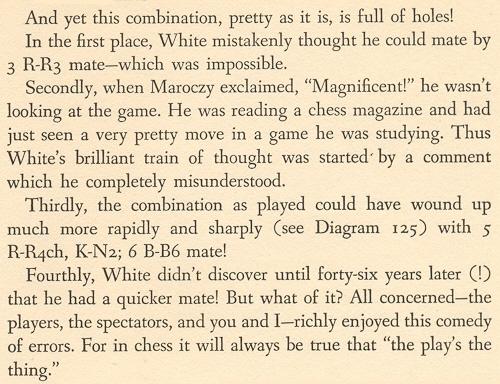

Reinfeld then wrote:

What was Reinfeld’s source for this story?

4889. What?

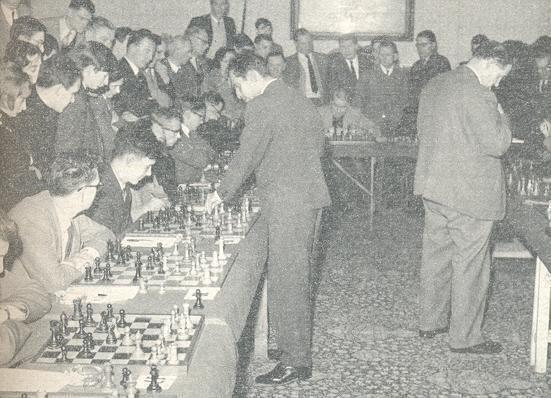

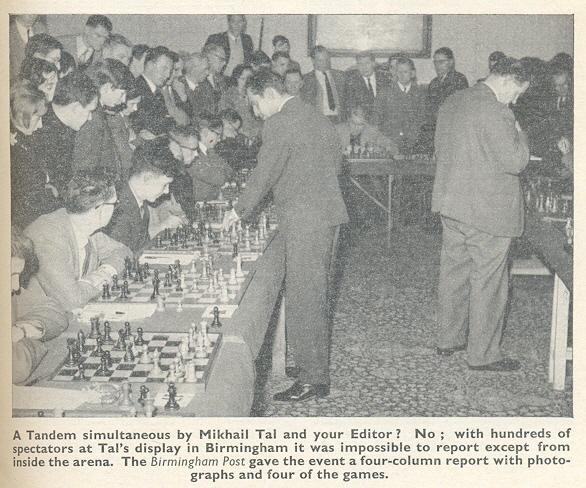

What is happening here?

4890. Lasker v Thomas

Position before 11 Qxh7+

As recorded in our Factfinder (under ‘Lasker v Thomas miniature’), C.N. items have frequently discussed a range of discrepancies in the famous game in which the black king was mated at g1. Many versions of the game-score exist, but here we focus on what Edward Lasker himself wrote. Five instances come to mind:

1) American Chess Bulletin, February 1918, page 28:

‘In 1912 I went to England in order to learn the English language, and my first visit, of course, was to the City of London Chess Club. I was lucky enough to win the following game against the club champion, G.A. Thomas, which gave me the best possible introduction: 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Bg5 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7 10 Qh5 Qe7 11 Qxh7+!! and mate in seven moves.’

2) Chess Pie, 1922, page 13:

‘The following game I consider the most beautiful I ever played … though it was not a tournament game and can, therefore, hardly be classed among the best games’. The score which Lasker then annotated had a different move-order up to move nine, the complete game being presented as follows: 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 Ne5 O-O 10 Qh5 Qe7 11 Qxh7+ Kxh7 12 Nxf6+ Kh6 13 Neg4+ Kg5 14 h4+ Kf4 15 g3+ Kf3 16 Be2+ Kg2 17 Rh2+ Kg1

18 Kd2 mate.

Lasker’s concluding remark was:

‘This game was played in the City of London Chess Club in 1912. A year later, Alekhine called my attention to the fact, discovered in Moscow, where he went over the game with Bernstein, that I could have mated in seven instead of eight moves by playing 16 Kf1 or O-O, as then Black would have been unable to prevent mate by 17 Nh2.’

After 15…Kf3

3) Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood by Edward Lasker (Philadelphia, 1942), pages 116-126:

Lasker gave the date as 1911 and described the encounter as ‘a so-called “five-minute” game, i.e. a game played with clocks as fast or as slowly as the players like, but with the condition that neither player must exceed the total time of the other by more than five minutes at any stage’.

The move-order was as in Chess Pie. Lasker related that some years after the game was played he received a letter from a chess club in Australia pointing out that, instead of 14 h4+, 14 f4+ mates one move faster (14 f4+ Kh4 15 g3+ Kh3 16 Bf1+ (or 16 O-O) Bg2 17 Nf2 mate), whereas 14…Kxf4 allows 15 g3+ Kf3 16 O-O mate or 15…Kg5 16 h4 mate.

After 13…Kg5

4) Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters by Edward Lasker (New York, 1951), pages 148-150:

Lasker showed the play from 11 Qxh7+ onwards and praised Thomas’ magnanimity in defeat. A footnote on page 149 referred readers to Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood for the detailed score.

5) Chess Life, June 1962, pages 126-127:

In article entitled ‘Fifty Years Ago…’ Lasker gave the game-score (with the same move-order as in Chess Pie and Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood) and stated that at move 14 he ‘had only about a minute to spare’. He mentioned the above quicker mates and commented as follows on his choice of 18 Kd2 rather than 18 O-O-O:

‘Instead of checkmating with Kd2 I could have done it by castling, which would perhaps have been more spectacular, as no player has ever been mated that way before, as far as I know. I actually considered castling, but the efficiency-minded engineer got the better of it and I played Kd2 which required moving only one piece.’

Mate by castling had, in fact, already been seen at that time, as noted in our Factfinder under ‘Castling, Mate by’.

Lasker continued in Chess Life:

‘Emanuel Lasker published this game in his chess column in the Berlin daily paper B.Z. am Mittag under the heading “The tragi-comic journey of the black king”. Apparently he did not see the shorter version 14 f4+ either. It was not called to my notice until seven years later, at the end of World War I, when I received a letter from Australia, where master Purdy had discovered the variation.’

This reference to ‘master Purdy’ is also strange, given that in 1919 (seven years after the game was played) C.J.S. Purdy was barely a teenager.

In Chess Life Edward Lasker then gave a different version of the ‘old man’ anecdote which had appeared on page 124 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood and supplied details of his arrival in the United States in late 1914 which are at variance with reports in that year’s American Chess Bulletin (e.g. the November 1914 issue, page 233).

The exact date of the Lasker v Thomas game was 29 October 1912 according to La Stratégie, January 1913, page 26. Lasker himself was responsible for so many mistakes and self-contradictions in his accounts of the game that it is hardly surprising that numerous other writers have misreported it too. To conclude here with just one instance not mentioned in our previous C.N. items: pages 163-164 of How to Win in the Middle Game of Chess by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1955) stated that the game was played in 1915, claimed that the opening moves were 1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nc3 Nf6, mentioned none of the faster mates and gave as the mating move not 18 Kd2 but 18 O-O-O.

Edward Lasker and George Thomas

4891. Schoolboy knowledge (C.N. 4863)

C.N. 4863 asked about the first occurrence in a chess context of the phrase often attributed to Botvinnik, ‘Every schoolboy knows that …’.

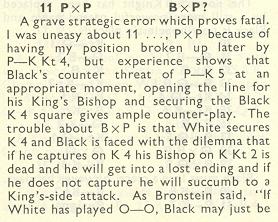

Taking up a lead from Norman Stephenson (Middlesbrough, England), who had a recollection of the remark in a UK chess magazine in relation to the game Botvinnik v Alexander, Munich Olympiad, 1958, we have found surprising passages in both CHESS and the BCM.

On page 30 of CHESS, 1 November 1958 P.H. Clarke wrote regarding round eight of the Olympiad finals:

‘England were beaten by the same margin as at Moscow [+0 =0 –4, as in the 1956 Olympiad]. Botvinnik won instructively.

All the Russians were horrified by Alexander’s 11th move, after which his game was strategically lost. Bronstein remarked, with some exaggeration, that every Russian schoolboy knows you must recapture with the pawn!’

C.H.O’D. Alexander annotated his loss on pages 30-31 of the January 1959 BCM, and below is a diagram of the position after 11 exf5, together with Alexander’s note on his reply, 11…Bxf5:

![]()

Alexander’s final words in this note are worth pondering:

‘As Bronstein said, “If White has played O-O, Black may just be able to afford BxP but if he has not it is fatal” – and every Russian schoolboy knows this!’

Were it not for what P.H. Clarke wrote in CHESS, we would automatically interpret the ‘schoolboy’ remark as Alexander’s own addition to the words of Bronstein which he had just quoted.

It is still unclear why the remark has been ascribed to Botvinnik. On page 113 of volume three of his trilogy Shakhmatnoe Tvorchestvo Botvinnika (Moscow, 1968) Botvinnik described 11…Bxf5 as ‘a typical strategic error in the King’s Indian Defence’ and stated that 11…gxf5 was forced, but made no reference to schoolboy knowledge:

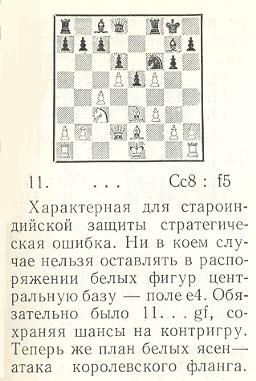

4892. A lovable book

On pages 213-215 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951) an extract from Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess was introduced by Reinfeld as follows:

‘Du Mont refers somewhere to Modern Ideas in Chess as a “lovable book”. The adjective comes as a surprise, but then I am reminded of the breathless eagerness with which I read Réti’s masterpiece as a schoolboy. The greatness of Réti’s achievement lies in this: his book not only gives us pleasure; it teaches us how to enjoy other books, other games. These modern ideas will always be modern.’

It seems likely that Reinfeld mixed up two books by Réti, because we recall that Julius du Mont made the following comment on page 50 of the March 1942 BCM:

‘Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board, a most lovable book … It is as good as reading a novel.’

Is any information available about M.A. Schwendemann, the translator of Masters of the Chess Board?

4893. Murray’s History

On page 5 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963) Fred Reinfeld was wide of the mark in stating that H.J.R. Murray ‘devoted a lifetime to a monumental history of chess’; Murray was still alive four decades after A History of Chess was published (see C.N. 3212 on page 200 of Chess Facts and Fables). Here we add that page 516 of the December 1912 BCM announced the forthcoming appearance of Murray’s book ‘upon which he has been engaged for more than 13 years’.

4894. Louis Eichborn

Marcelo Semprevivo (Buenos Aires) raises the subject of Louis Eichborn, whose name is well known for a large number of published victories over Adolf Anderssen. The rather mysterious Eichborn has been mentioned in C.N. a number of times (see the Factfinder), but does any article exist which authoritatively draws together the essentials of his life?

4895. Araucaria imbricata (C.N. 4881)

This was the frontispiece of Trees & Shrubs for English Plantations by Augustus Mongredien (London, 1870). Below is the title page of our copy, inscribed by him:

4896. Schoolboy knowledge (C.N.s 4863 & 4891)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘I was in Munich in 1958, and my memory is that Bronstein made the “schoolboy” remark. It is the type of phrase characteristic of Bronstein but not typical of Botvinnik. I can dimly recall Alexander retailing the criticism, with some zest.’

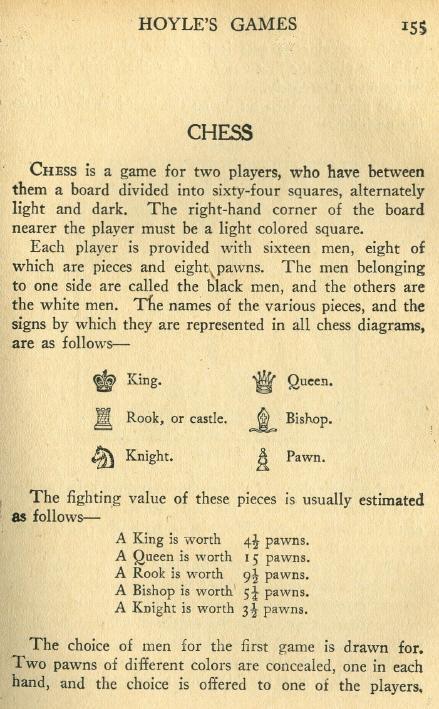

4897. The value of the pieces

Matt Goddard (Hiram, GA, USA) mentions a peculiar list of piece values on page 155 of Hoyle’s Complete and Authoritative Book of Games (the 1952 edition from Garden City Books, Garden City, New York, originally published in 1907 by the McClure Company):

Our correspondent writes:

‘Are there other examples where these were given as the common values, and where specifically did these values originate?’

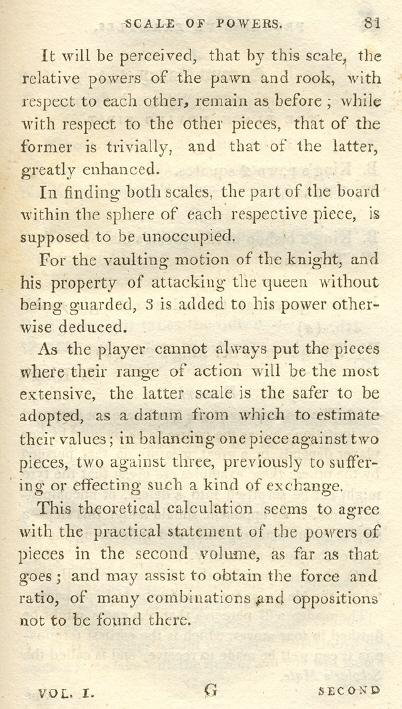

In no other edition of Hoyle that we have consulted is the queen valued at more than ten pawns, and the evaluations given in the illustration above are certainly unauthoritative. Below we briefly list some further examples (pre-Second World War) of how this subject has been treated.

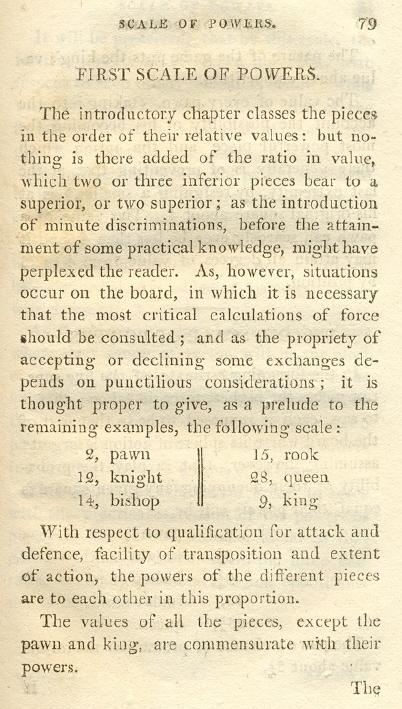

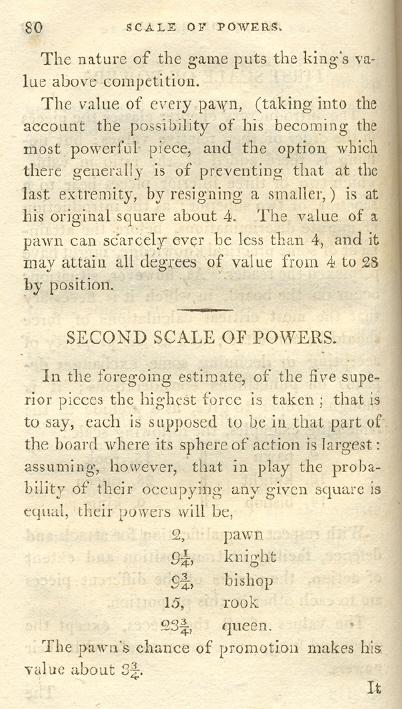

- Pages 79-81 of Studies of Chess by Peter Pratt (London, 1803):

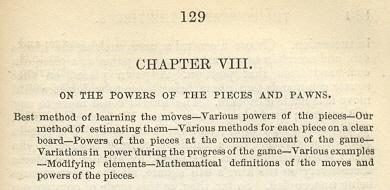

- Chapter VIII of Amusements in Chess by Charles Tomlinson (London, 1845) had a chapter ‘On the powers of the pieces and pawns’ (pages 129-138) which gave a number of lists, according to mobility.

The ‘final relative values’ (page 136) were:

pawn: 1.00

knight: 3.05

bishop: 3.50

rook: 5.48

queen: 9.94.

- ‘Vom Tauschwerthe der Steine im Schach’ by v. Oppen, Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1847, pages 8-13, March 1847, pages 70-79 and May 1847, pages 141-149. Detailed treatment which featured an overview of many previous attempts to evaluate the pieces.

- Page 34 of The Chess-Player’s Handbook by Howard Staunton (London, 1847). The values he gave were those of Tomlinson (see above).

- ‘Ueber den Tauschwerth der Steine’ by Alexandre, Deutsche Schachzeitung, July 1850, pages 225-227. Follow-up work by Alexandre to what had appeared in the magazine in 1847.

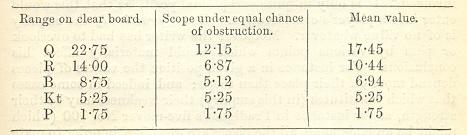

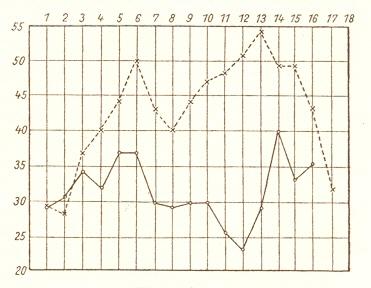

- ‘On the Relative Value of the Pieces’ by J. Pierce, BCM, March 1884, pages 78-81. Pierce summarized ‘a very interesting and able paper by Mr Biddle … in the Educational Times’ and included on page 79 the following chart:

Pierce then explained the conclusions in the Biddle paper:

‘The author lays down the law that the entire value of a piece is the product of its separate values for attack and defence. He shows that the value of a piece for defensive purposes varies inversely as its entire value and directly as its mean scope. Hence the square of the entire value is equal to the product of its attacking value and mean scope.

Thus we get ultimately the entire values Q=10, R=5.84, B=3.53, Kt=2.89, P=.5.’

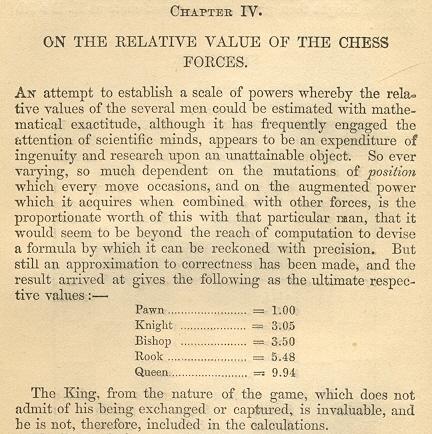

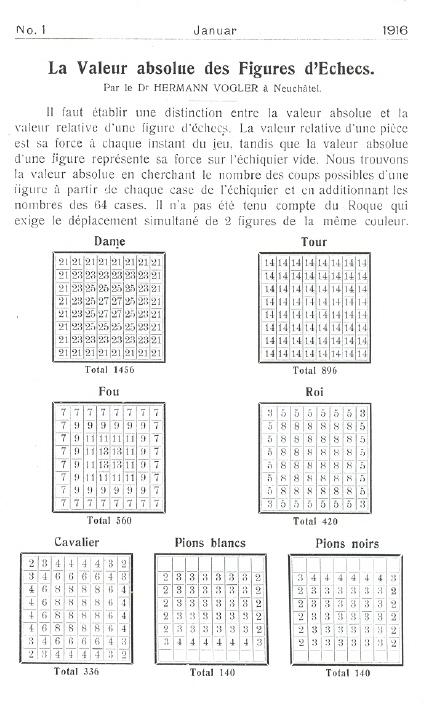

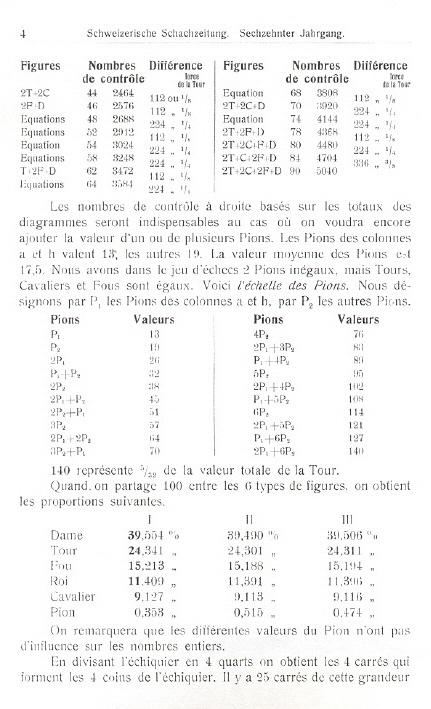

- ‘La Valeur absolue des Figures d’Echecs’ by Hermann Vogler, Schweizerische Schachzeitung, January 1916, pages 1-6. Two sample pages are given below:

Page 83 of the March 1916 BCM gave a tepid reception to Vogler’s ‘curious’ article, although on page 125 of the April 1916 issue a reader, S.H. Gould, opined that the BCM had dismissed it too lightly. Vogler’s article was reproduced on pages 65-70 of La Stratégie, March 1916.

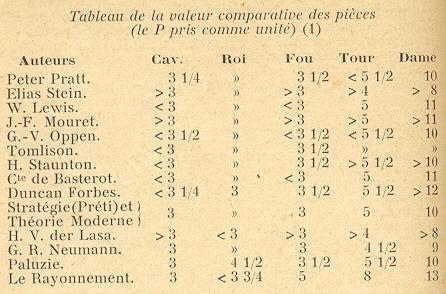

- In La Stratégie, May 1916, pages 129-132, Anatole Mouterde contributed an article entitled ‘De la valeur comparative des pièces’ which concluded with this comparative chart:

- BCM, March 1922, page 95 and July 1922, page 271: brief mathematical items, notably on the respective values of the bishop and knight.

- ‘Zahlenwerte der Schachfiguren’ by Dr Kemmerling, Deutsche Schachzeitung, March 1935, pages 65-68 presented calculations of the pieces’ values. Page 131 of the May 1935 issue had a brief follow-up item based on calculations made by Curt L’hermet in the Magdeburgische Zeitung of 23 November 1913.

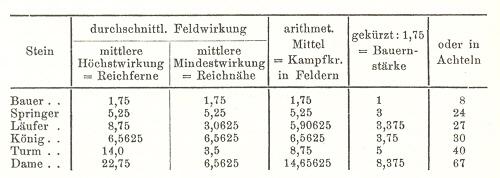

- ‘Die Kampfkraft der Schachsteine’ by Gerhard Pusch, Deutsche Schachzeitung, April 1936, pages 97-100. Detailed mathematical calculations which concluded with this table:

The above listings are, of course, by no means exhaustive but offer an overview of the old-timers’ attempts to allocate exact values to the chess pieces.

4898. Find the win (C.N. 4888)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) points out that Reinfeld’s account is a summary of an article by Josef Krejcik entitled ‘Ein einmaliger Partieschluß’ on page 179 of the 11/1953 Schach-Echo. Krejcik stated that he won the game from Jakob Bendiner in March 1907 and that Maróczy’s comment ‘magnificent!’ (‘prächtig’) was prompted by a problem of Pauly’s in the Deutsches Wochenschach. Page 212 of the 13/1953 Schach-Echo reported that several readers had noted the faster mate 5 Rh4+ Kg7 6 Bf6.

We cannot explain why Krecjik gave two different positions or why, on page 14 of the March 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung, he described his opponent as ‘a well-known grandmaster’.

4899. What? (C.N. 4889)

The photograph in C.N. 4889 appeared on page 187 of the 29 February 1964 issue of CHESS (editor: B.H. Wood):

4900. Napoleon Marache

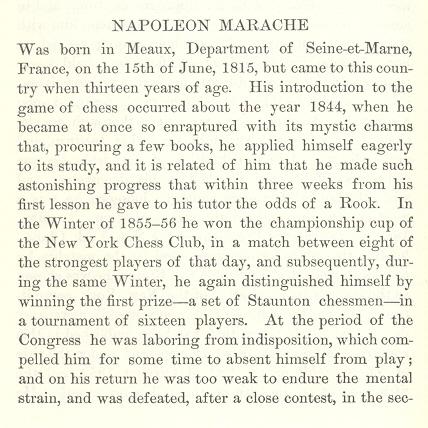

Napoleon Marache

From page 28 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

‘Napoleon Marache made such rapid strides in assimilating chess that he was able, three weeks after his first lesson, to give his tutor the odds of a rook.’

Chernev did not specify his source, but we imagine that it was page 46 of The Fifth American Chess Congress by Charles A. Gilberg (New York, 1881):

4901. Connection

What is the connection between these two illustrations?

4902. The value of the pieces (C.N. 4897)

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘Page 57 of my publication The Hall-of-Fame History of US Chess (1998) has an article tracing the scale of powers that were given in Amusements in Chess and in Staunton to an earlier source: an 1817 edition of Philidor’s analysis, apparently done by Peter Pratt. In that edition, Pratt devoted 40 pages to mathematical analysis of various factors, leading to his concluding scale of Q=9.94, R=5.48, B=3.5, N=3.05, P=1. He suggested rounding off the scale, but Staunton and Steinitz printed it with full decimal places.

I have subsequently found that Pratt, as early as 1805 and probably earlier, gave two different scales, based on different lines of reasoning. The first scale had P=2, N=12, B=14, R=15, Q=28, K=9, whereas his second scale was P=2, N=9.25, B=9.75, R=15, Q=23.75, no K value. Apparently Pratt later developed the mathematical analysis printed in 1817. The same figures were used not only by Staunton in his Handbook but also by Steinitz (on page xxxiii of The Modern Chess Instructor), and ultimately became our modern scale.’

4903. The Balaclava Charge

‘What is the “Balaclava Charge” on the chess board?’, asks Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands). Our correspondent quotes a passage (abridged by us below, as indicated by ellipses) from theHartford Times, 13 December 1873:

‘Chess Tournament

An English paper, the Suffolk Mercury, gives a long account of a chess tournament that lately took place at Ipswich, England. We quote:

“‘Ye game and play of ye chesse’ – the subject of the second book printed in England, the Bible being the first – has been exemplified on an unusual scale at the Ipswich Town Hall this week. The East Anglian amateurs have mustered in force to contend in a grand tournament, originated by the flourishing and prosperous chess club which meets at the Mechanics’ Institute in this town. Through the liberality of the residents of the district the committee were enabled to offer more than £60 in prizes, and though chess is the one game which needs no stimulus but the quest of honor and victory, the prospect of substantial trophies to commemorate success had doubtless an influence in drawing together such a concourse of players as has never met before in the eastern counties …

Additional interest was lent to the proceedings by the presence throughout the meeting of Mr Blackburne, the famous blindfold player, who tied for the first prize at Vienna, and who gratified several skillful amateurs with specimens of his play. Mr Blackburne won two or three hardly-contested games of Mr Howard Taylor, of Norwich (author of Chess Brilliants), but was unexpectedly vanquished by Mr Charles Gocher, of Ipswich, who treated him with a local invention, known as the ‘Balaclava Charge’ – a radically unsound but slashing opening, to which the celebrated player succumbed …”’

We note that the ‘East Anglian Chess Tournament’ was announced on page 348 of the October 1873 Chess Player’s Chronicle as scheduled for 5-7 November.

4904. Pillsbury v Edwards

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Pages 9-10 of Chess World, 1 January 1949 had a feature on ‘Gippsland’s chess king, veteran T.J. Edwards’:

‘… Without too much conventional biographical detail, we now take our readers back to 1901, and set them down in the famous old city of Bath. One of the most glamorous chess masters of all time is giving a “simul” there. It’s Harry Nelson Pillsbury. Some of his opponents have tumbled their kings already. Suddenly Pillsbury is seen to be dismantling a position. He is actually restoring it to an earlier stage. Then he beckons the onlookers, and asks them, “Don’t you think I’ve got the best of it here?”

They all agree that he certainly has (see diagram) as he is threatening Qxh7+ and what not.

“Now”, says Pillsbury to his youthful opponent, “Play through your finish again. And the two repeat, for the edification of the onlookers, the combination which has just ended in real earnest. Here is the diagram of the restored position.

White: H.N. Pillsbury Black: T.J. Edwards (Black to move)

Having already indicated the identity of the youthful opponent, we give the moves.

18…e4 19 Nxe4 Bxf3 20 Qxf3 (If 20 Ng5, simply 20…Qxg5 21 Qxh7+ Kf8 22 Qh8+ Ke7. Or, in this, 22 g3 Nf4.) 20…Bxh2+ 21 Kxh2 Rh6+ 22 Kg1 Qh4 23 Qh3 Nf4 24 Qxh4 Ne2+ 25 Kh2 Rxh4 mate.

Then Pillsbury shook hands, saying, “Congratulations – brilliant little combination – took me completely by surprise.”

So that was Pillsbury. The chess world was not permitted to keep him long. A few years later he died, aged 33.’

It would seem that this game was played not in 1901 but in 1903 (on 31 January). Defeat by Pillsbury at the hands of T.J. Edwards was mentioned on page 23 of the 6/2000 Quarterly for Chess History.

4905. Ilmar Raud and Argentinian chess

When only in his mid-teens the Estonian player Ilmar Raud (born in 1913) had ‘already made a name for himself’, according to Paul Keres on page 12 of volume one (‘The Early Games of Paul Keres’) ofGrandmaster of Chess (London, 1964).

Buenos Aires, 1939. From left to right: P. Schmidt, G. Friedemann, P. Keres, I. Raud, J. Türn

After participating in the 1939 Olympiad Raud remained in Argentina but less than two years later he was dead, at the age of 28. Page 246 of the August 1941 issue of El Ajedrez Americano reported that he was ‘víctima de una repentina dolencia, que motivó su internación en un sanatorio’, whereas almost the entire first page of the October 1941 CHESS was devoted to an account of his last months, under the heading ‘Raud, the young Esthonian master, starves to death’. Below are the details of his demise as reported by CHESS:

‘[On 29 June 1941] he left his poor lodging-house never to return. He was found wandering in the streets and was arrested by the police. It was said there was a fight, and visitors subsequently observed obvious evidence of blows. He spent a bitterly cold night in the police yard, and the next day was sent to a lunatic asylum, where he died at 2 a.m., on 13 July, at the early age of 27 [sic]. The doctor’s certificate gave, as cause of death, general debility and typhoid fever, but the general verdict is – starvation. His body was cremated, and the ashes have been conveyed by the Esthonian consulate to Europe.’

The article strongly criticized the alleged treatment of players such as Raud in tournaments:

‘Conditions in South America’s chess world are extraordinary. Grau has achieved a position of extraordinary power and influence and is virtually dictator of Argentine chess; it is authentically stated that his chess organizing activities have netted him at least £5,000 in two years. Yet tournament after tournament goes through in the most haphazard and unsatisfactory fashion.’

As ever, we invite substantiation, or invalidation, of these assertions.

Ilmar Raud

The two photographs reproduced here come from Meie Keres by Valter Heuer (Tallinn, 1977). A group photograph (Buenos Aires, 1939) with Raud seated next to Keres is on page 106 of Paul Keres Photographs and Games (Tallinn, 1995).

The above-mentioned obituary in El Ajedrez Americano illustrated Raud’s play with his short victory as Black over Erik Lundin at the Buenos Aires Olympiad (24 August 1939), and the same game was given on page 50 of ¡¡Enroque!!, August 1941. Both Argentinian magazines had a slightly different game-score from the customary version, by omitting 10…c6 11 Bd3 and thereby having Lundin resign after 25…Ne4 (and not 26…Ne4). The game is in most databases.

4906. Ron Thacker

Robert Pearson (Reno, NV, USA) is seeking information about Ron Thacker, who played against Bobby Fischer in the third round of the 1957 US Junior Championship in San Francisco.

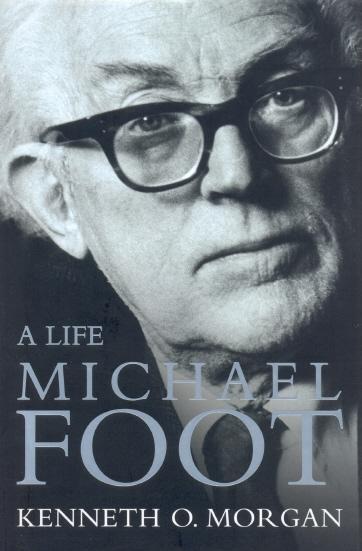

4907. Michael Foot

In C.N. 4203 Lord Morgan presented a tribute to his father, that exceptional chess writer D.J. Morgan (1894-1978), and below we quote a brief chess-related passage from Lord Morgan’s latest book, abiography of Michael Foot. Born in 1913, the British politician was the leader of the Labour Party from 1980 to 1983, and the dust jacket carries a fine quotation by him (from page 489): ‘Men of power have no time to read; yet the men who do not read are unfit for power.’

The chess text appears on pages 109-110 and relates to Foot’s first term in the House of Commons, to which he was elected in 1945:

‘Foot also liked the parliamentary atmosphere, the chatter and conspiracy in smoking room and tea room, the ready access to Fleet Street friends. He enjoyed too some of the extra-mural activities, especially the group of MPs who played chess. Leslie Hale was his favoured opponent. Foot was recognized as being amongst the best parliamentary players, though it was agreed that the strongest was Julius Silverman. Others of note were Douglas Jay, Reginald Paget, Maurice Edelman and Maurice Orbach, with Jim Callaghan another, less talented, enthusiast. The world’s dominant players were Russian, and Foot met several grandmasters when an international tournament was held in London in 1946.’

4908. The Bismarck family

Olaf Teschke (Berlin) quotes the following passage from page 106 of Living Leaders of the World (Chicago and St Louis, 1889):

‘The grimness and ruthless ambition of Otto von Bismarck must have come down to him from his ancestors who fought and suffered in the days of Wallenstein and Tilly. Certainly they did not appear in his immediate parents. His father was a handsome, merry sportsman and courtier. His mother was a proud and beautiful dame of the old school, highly intellectual, gifted with graces and, withal, one of the most skilful chessplayers of the time …’

Our correspondent asks on what grounds that last claim was made.

4909. Bookplates

It is a while since a chess-related bookplate was presented; the one below (Leonard Herring) comes from Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England).

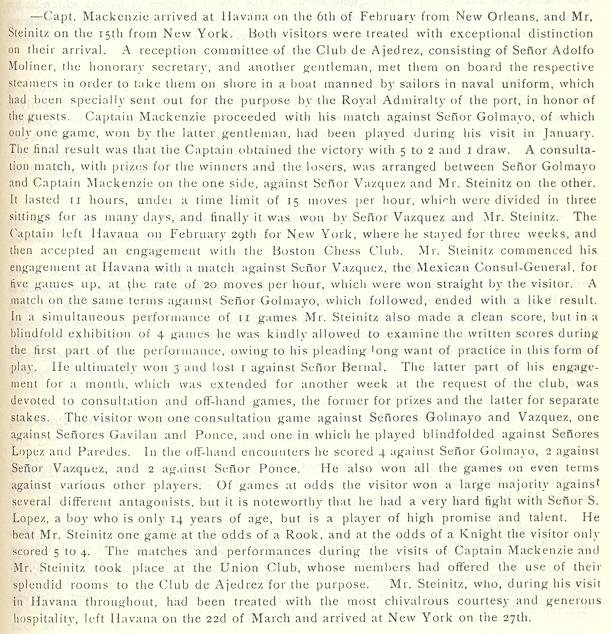

4910. Steinitz in Havana

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) draws attention to a news item in the chess column on page 4 of the Morning Chronicle (Quebec), 24 May 1888:

‘In a match of five games, at the odds of a Kt, with Herr Steinitz, Señor S. Lopez, of Havana, aged 14, succeeded in winning four games. The champion pronounces the youth a promising player.’

We give below the account that had appeared in Steinitz’s International Chess Magazine, April 1888, page 79. The reference to the 14-year-old boy, together with his actual score against Steinitz, begins nine lines from the end.

4911. Fermat’s Last Theorem

Steve Giddins (Rochester, England) refers to ‘the fascinating book’ Fermat’s Last Theorem by Simon Singh (London, 1997):

‘It tells the story of the 350-year search for Fermat’s missing proof, and some interesting references are worth noting by chess enthusiasts.

In discussing the craze for puzzles in the second half of the nineteenth century, pages 138-142 tell of Sam Loyd, described by Singh as “… the greatest riddler of them all”. No mention is made of Loyd’s prowess as a chess problemist, but considerable detail is given on the famous “14 x 15 tiles” puzzle (now known not to be his invention, as reported in C.N.s 4406 and 4749).

Another chess composer referred to in the book – again without mention of his chess connection – is Noam Elkies, the Israeli endgame study composer. The book Endgame Virtuosity – a Collection of 222 Israeli Chess Studies (Vienna, 1996) gives some biographical details about Elkies, a true mathematics genius. Born in 1966, he gained a doctorate in mathematics in 1987 and became, in 1993, the youngest-ever full professor of Harvard. Singh’s book (page 178) describes how, in 1988, Elkies refuted the 200-year-old Euler’s Proposition. Pages 293-295 explain how Elkies was involved, indirectly, in a famous April Fool’s trick in 1994, when a colleague distributed an e-mail message which claimed that Elkies had refuted Fermat’s Last Theorem.

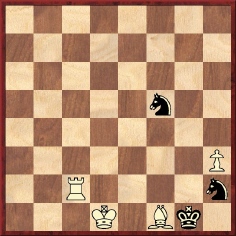

The following is a spectacular example of Elkies’ prowess as a study composer:

White to play and win.

First Honourable Mention, Israel Ring Tourney, 19861 b8(Q) Rxb3+ (1…c1(Q) 2 Qe5+ mates) 2 Qxb3 c1(N)+ 3 Kc2 Nxb3 4 Re8+ (4 Kxb3 Rf2 draws) 4…Kf2 5 Rf8+ Kg2 6 Rxf1 Nd4+ 7 Kd3 Nf3 8 Ke3 (or 8 Ke2) 8…Nxh2

9 Rh1 Kxh1 10 Kf2 and wins.’

4912. The lady visitor

Before proceeding, readers are invited to identify the five people in the above photograph.

It was taken during a small tournament in Bladel, the Netherlands in 1969, and the opening 1 d4 f5 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Nh6, played in one of the games, was christened the Bladel Variation. The average age of the participants was nearly 70, and the photograph shows all four of them: M. Euwe is facing K.Opočenský, and in the top right-hand corner are H. Müller and S. Flohr. The Dutch Defence game was a 12-move draw between Flohr and Euwe. Standing next to the Dutchman is the widow of Richard Réti; the tournament commemorated the 40th anniversary of his death.

The photograph comes from page 14 of CHESS, September 1969, which reported:

‘As an additional gesture, Réti’s widow has also been invited over from Moscow. She attended every round and watched all the games with great interest.’

Biographical information about her will be appreciated. On page 194 of the July 1926 Wiener Schachzeitung Hans Kmoch remarked that from the Moscow, 1925 tournament Réti brought back not only a ‘beauty prize’ for his game against Romanovsky but also a beautiful young Russian as his wife:

‘… Réti, der aus Moskau nicht nur den Schönheitspreis für seine Partie gegen Romanowski, sondern auch eine schöne junge Russin als Gattin mitgebracht hat, mit der er nun seine Hochzeitsreise unternimmt.’

On page 3 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess (London, 1954) Harry Golombek referred to Kmoch’s comment, and page 129 mentioned again the prize won by Réti for his game against Romanovsky. However, Golombek went astray on page 37 of Chess Treasury of the Air by T. Tiller (Harmondsworth, 1966) by stating that Réti did not win such a prize in the Moscow, 1925 tournament. Referring to the opening ceremony of the Botvinnik v Tal world championship match in 1960 Golombek wrote:

‘One of the items this time was a prelude for pianoforte dedicated to Tal and Botvinnik. Afterwards I was introduced to the composer who, surprisingly enough, wasn’t a chessplayer. His connexion with the chess world was that his wife was the former Mrs Réti. Despite the passage of some 35 years since the remark was made, on looking at her I realized what was meant when it was said that Réti may not have won a beauty prize over the board at Moscow, 1925, but he had come away with one all the same. For this was the beautiful Russian girl whom he had met and married in Moscow that year.’

Can the name of Mrs Réti’s later husband be established (possibly from a souvenir programme for the opening ceremony of the 1960 match)?

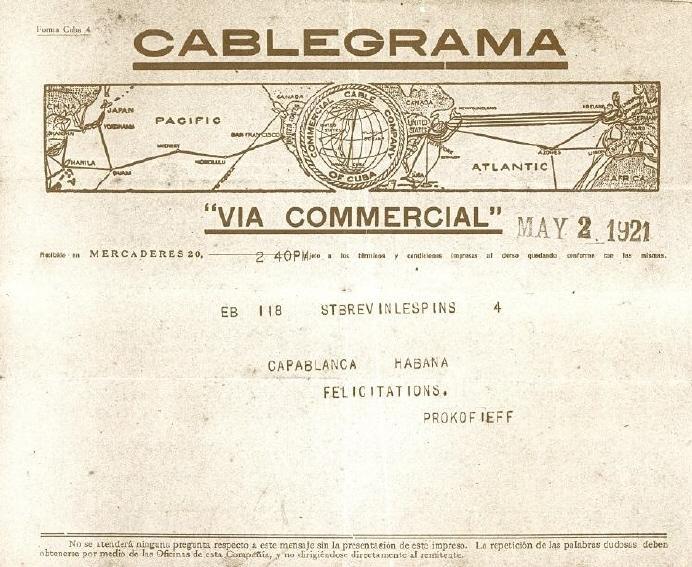

4913. Botvinnik on Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev

The following article by Mikhail Botvinnik was published on pages 281-283 of S. Prokofiev Autobiography Articles Reminiscences (Moscow, 1959). It was dated 1954, the year after Prokofiev’s death.

‘My first introduction to Prokofiev and his music occurred at one of the musical appreciation lessons that were a regular part of the curriculum at school No. 157 in Leningrad which I attended in the early twenties. These lessons were essentially little chamber concerts with explanations by the music teacher. As a rule we were given classical music, but one day our teacher said that she was going to play something rather out of the ordinary.

She told us about a young composer named Sergei Prokofiev and his original style. “It is impossible to be indifferent to his music”, she told us. “Some people believe him to be exceptionally talented, others disapprove of him altogether. When I addressed a gathering of music teachers recently and announced that I was going to play the music of Prokofiev I was given an extremely chill reception. But when I had finished playing, the audience applauded wildly and I had to play an encore. I shall play the same piece to you now.”

If I am not mistaken the name of the piece was Despair. It made a deep impression on all of us. Unfortunately I have never heard it since; if I had I should recognize it at once.

I met Prokofiev in 1936 at the height of the Third International Chess Tournament in Moscow. He was a first-rate chessplayer himself and never missed a match. His position in the tournament was a delicate one and he maintained a strictly neutral attitude throughout, for while his sympathies were naturally with me as the young Soviet champion, he could not wish for the defeat of the ex-world champion Capablanca, who was a personal friend of his.

Several months later Capablanca and I shared first place at the tournament in Nottingham, England. When the tournament was over I received a telegram of congratulations from Sergei Sergeyevich. I was naturally very pleased and, without thinking, I showed the wire to Capablanca, who was with me at the time. At once I saw that I had made a mistake – from the expression on Capablanca’s face I realized he had not received a wire from Prokofiev. Two hours later Capablanca came to me beaming – he had received a telegram too. Of course, Sergei Sergeyevich had sent both wires at the same time, but evidently the Moscow telegraph office clerks had felt that the Soviet champion ought to get his message first.

Sergei Sergeyevich was passionately fond of chess. He took part in the chess activity of the Central Art Workers’ Club. Moscow chessplayers still remember his rather unique match with David Oistrakh – the winner was awarded the Art Workers’ Club prize and the loser had to give a concert for the club members.

I played chess with Prokofiev several times. He played a very vigorous, forthright game. His usual method was to launch an attack which he conducted cleverly and ingeniously. He obviously did not care for defence tactics. His illness did not lessen his interest in chess. In May 1949 the well-known chessplayer J.G. Rokhlin and I paid a visit to Prokofiev at his country place at Nikolina Gora. Sergei Sergeyevich was ill in bed and looked very poorly, but as soon as he saw Rokhlin he livened up. “Where is that volume of the 1894 Steinitz and Lasker chess match you promised me?”, he demanded. Poor Rokhlin, who had clearly forgotten all about it, was much embarrassed.

In the summer of 1951 Sergei Sergeyevich entered as one of the participants in a demonstration of simultaneous play I was to give at Nikolina Gora. His doctors, however, forbade it, but that did not prevent Prokofiev from following the games with his usual avid interest. I believe that was the last chess contest he ever attended.’

The photograph of Prokofiev at the start of the present item appeared in the same book. Botvinnik also related the 1936 and 1949 episodes on pages 55 and 126 of his autobiography Achieving the Aim(Oxford, 1981). See, furthermore, the references to Prokofiev in the Factfinder.

As noted on page 313 of our book on Capablanca, Prokofiev sent a one-word message of congratulations when the Cuban defeated Lasker in 1921:

4914. Noam Elkies (C.N. 4911)

Simon Singh (London) draws our attention to a recent mathematical proof in which Noam Elkies was involved.

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘The composition by Noam Elkies quoted in C.N. 4911 is an excellent illustration of how a composer can improve a study by adding interesting introductory play. In Shakhmaty v SSSR, 1976 the late Ernest Pogosyants published this position:

White wins with 1 Rh1.

Of course, this is more a sketch for a study rather than a finished work, but I do not know if Pogosyants ever built on it. As there is no mention of this forerunner in Endgame Virtuosity, Noam Elkies was probably unaware of it when he composed his study. Another composer who added introductory play was Ignace Vandecasteele, in Finales y Temas, 2003:

White to move and win.

1 Rg2+ Kh1 2 Rf2 Ne3+ 3 Ke2 Nexf1 4 Rxf1+ Kg2 5 Rh1 Kxh1 6 Kf2 and wins. Brian Stephenson checked the Pogosyants source for me in the van der Heijden database, and while doing so found the Vandecasteele composition.

One remarkable achievement of Noam Elkies was winning the individual title at the World Chess Solving Championship at Tel Aviv in 1996, in his first appearance in the event.’

4915. Chess philosophy

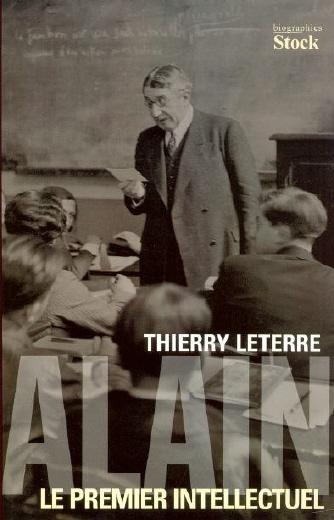

From Bradley J. Willis (Edmonton, Canada):

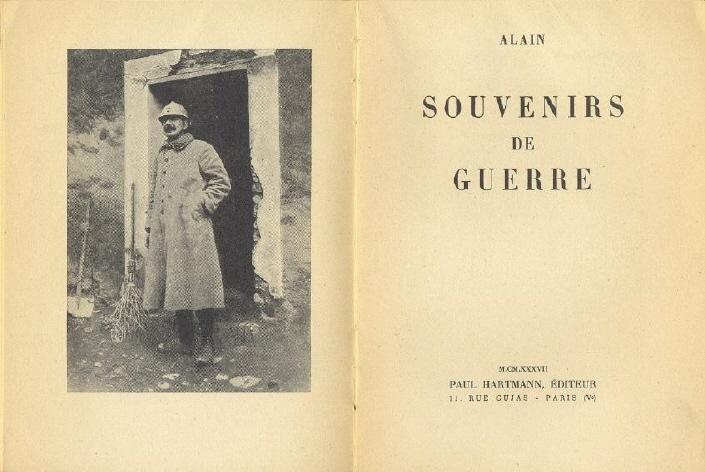

‘Thierry Leterre’s biography Alain Le premier intellectuel (Paris, 2006) mentions on page 175 that Alain, the nom de plume of the philosopher Emile Chartier (1868-1951), was a keen chessplayer. The following passage comes from pages 166-167 of Alain’s Souvenirs de guerre (Paris, 1937):

“J’ai enseigné le jeu d’échecs à un bon nombre de camarades, pendant cette guerre. Et j’ai remarqué une erreur assez commune, c’est que, quand ils avaient compris les règles du jeu, ils se disaient sûrs de n’être plus jamais battus. Ces jeunes gens avaient une haute idée de l’esprit. Ce qui est à remarquer dans le jeu d’échecs, c’est que, comme il n’y a que combinaison, sans aucun événement, tout devrait être prévu et calculé; mais la complication des rapports fait aussitôt une sorte d’Univers, quoique fermé, où les surprises abondent; c’est comme un hasard de main d’homme, et il n’en est que plus émouvant. Sans aucun doute les joueurs qui calculent tout, s’il y en a, perdent le plaisir du jeu. Pour moi, et devant mes naïfs adversaires, je créais des paniques et des surprises; je jouais sur les passions. Toutefois avec Mattéi, comme avec deux ou trois autres, j’apprenais que la force d’âme ne répare point les fautes. En ce juste milieu entre la témérité et le calcul, j’ai tiré de ce jeu les plus vifs plaisirs peut-être qu’il peut donner. Pris ainsi et moyennement, il est bien l’image de la guerre.”

I found one of Alain’s propos (a short epigrammatic essay-form invented by him) that appears to refer in passing to his games with Mattéi, a fellow-soldier who was convalescing with him in the same field-hospital in 1916. (Alain voluntarily signed up, at the age of 46, and fought for more than three years in the Great War as an artillery spotter, telephone operator for the artillery, and brigadier, before being wounded too severely to carry on. He was a pacifist, but believed that there was a duty to fight if one’s country was at war.’

Our correspondent asks if anything further is known about Alain as a chessplayer.

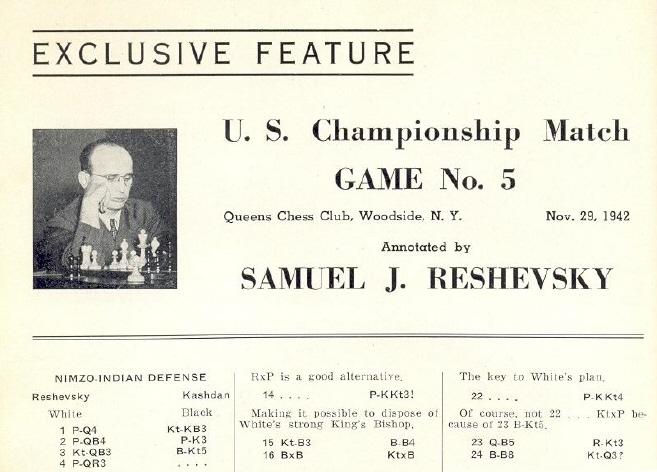

4916. Reshevsky’s middle name

‘Samuel Herman Reshevsky’ is the widely-used full version of the master’s name, but what is the exact basis for the ‘Herman’? How far back can its use be traced, and on what occasions did Reshevsky himself write it?

We raise the matter after noting that a match report by Kenneth Harkness on page 3 of the January 1943 Chess Review referred to ‘Samuel J. Reshevsky’ and that on page 6 the same initial appeared prominently in the heading to an article by Reshevsky himself:

4917. Noam Elkies (C.N.s 4911 & 4914)

From Noam Elkies (Cambridge, MA, USA):

‘I was indeed unaware of the Pogosyants predecessor when I composed the study, but I did learn of it subsequently. Curiously, this is not the only time that one of my studies turned out to develop a Pogosyants sketch: the same is true of the even better Castling study that won first prize in the 1987 Israel Ring Tourney:

White to move and win

For the solution see the last page of my article “Endgame Explorations 11: Castling”. (The prize was awarded in spite of the Pogosyants anticipation, which the judge had come across, and despite a dual in the 5…Kh1 variation.)

My only other comment on these two C.N. items is that the Euler statement that I disproved was a conjecture, not a proposition. The word “proposition” has a technical meaning in mathematics, and is not used unless the statement in question has been actually proved; naturally if Euler or anybody else had actually proved his conjecture then it would be impossible to disprove it.’

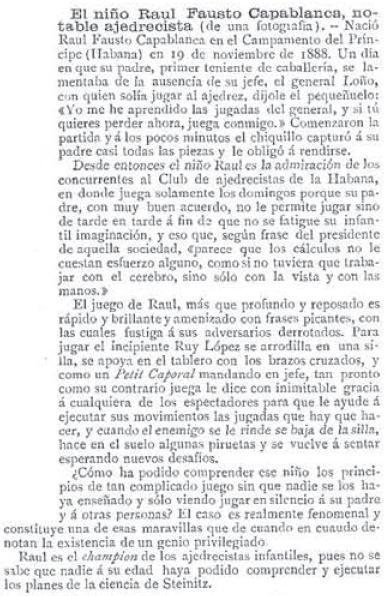

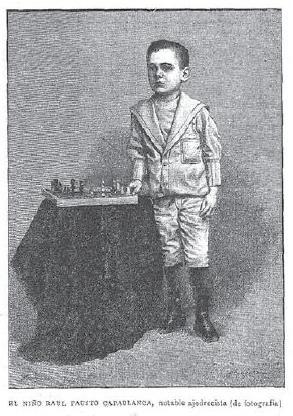

4918. Capablanca in the 1890s

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) sends the following from the 11 December 1893 issue of a weekly magazine published in Barcelona, La Ilustración Artística, pages 802 (text) and 808 (engraving):

Mr Sánchez comments:

‘This may be the earliest notice of Capablanca outside of Cuba, coming a couple of months after Vázquez’s report in El Fígaro, which is its likely source. (I am following page 3 of your Capablanca book.)’

Andrés Clemente Vázquez wrote two notable articles on Capablanca in the Cuban periodical El Fígaro (8 October 1893, pages 431-432, and March 1897, page 142). The former also dealt with the Mexican chess prodigy Andrés Ludovico Viesca (see pages 52-53 of Chess Explorations), and the full article was reproduced on pages 29-35 of the June 1911 issue of the Cuban magazine Crónica de Ajedrez.

Part of the account of Capablanca’s introduction to chess (on which the above report in La Ilustración Artística was indeed clearly based) reads as follows:

‘Raúl Fausto Capablanca nació en el Campamento del Príncipe (Habana), el 19 de Noviembre de 1888. Un día en que su Sr. Padre, el pundonoroso primer Teniente de Caballería (de la Cabaña) D. José Capablanca y Fernández, se lamentaba de la ausencia de su ilustre Jefe y respe[c]table amigo nuestro, el Excmo Sr. General, D. F. Loño, con cuya particular amistad se ha honrado, y de quien solía ser, frente al tablero de ajedrez, antagonista y víctima, su pequeñuelo le dijo: “Yo me he aprendido las jugadas del General, y si tú quieres perder ahora, juega conmigo.” – Veremos – le contestó el padre – lo que se te ocurre hacer con los peones, las torres y los caballos; – y en pocos minutos el chiquillo le capturó casi todas las piezas y le obligó á rendirse.’

In short, Capablanca said to his father, ‘I have learned the moves [of or from?] the General, and if you want to lose now, play with me’. The boy was referring to his father’s frequent chess opponent, General Loño. The father and son then played a game, and in a few minutes Capablanca had captured virtually all his father’s pieces and compelled him to resign. There are, of course, many other versions of Capablanca’s introduction to chess, but this one was published before he was five years old.

Below we reproduce Vázquez’s second (1897) article:

An English translation of part of this article was given on pages 3-4 of our book on Capablanca. As regards the picture, it may be recalled that a good-quality version was published on page 27 ofChessworld, May-June 1964:

4919. Group photograph

Identifying everyone in this photograph is far from easy, and readers’ assistance will be appreciated.

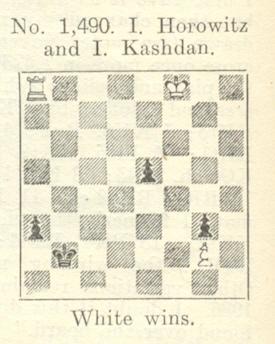

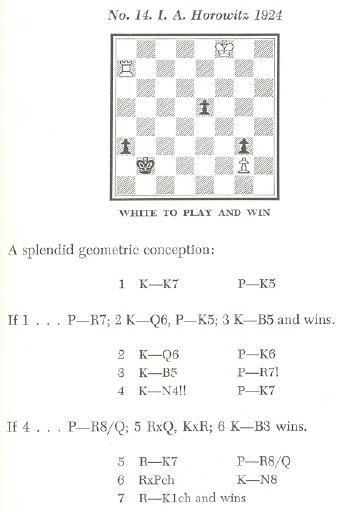

4920. Horowitz (and Kashdan)

Chess Amateur, October 1927, page 10

Chess Amateur, October 1927, page 10

The Macmillan Handbook of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1956), page 203

The second item comes from a chapter entitled ‘Composed Chess Endings’ by P.L. Rothenberg. What is the explanation for the absence of Kashdan’s name?

4921. Who?

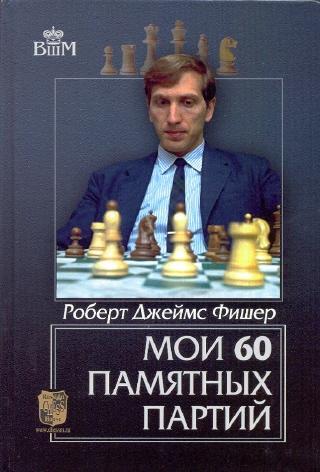

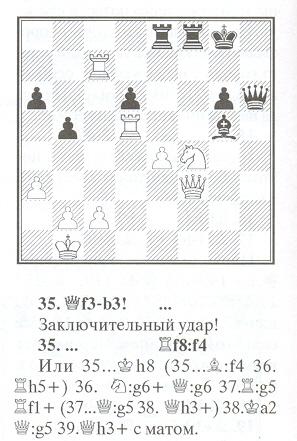

4922. Fischer v Bolbochán

The Russian translation of Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games has been reissued (Moscow, 2006), and in Fischer v Bolbochán, Stockholm, 1962 the non-existent mate remains (page 128):

How many books and magazines had the same analytical mistake before the 1995 Batsford edition of Fischer’s book? At the moment, our feature article Fischer’s Fury mentions half a dozen instances.

4923. A forgotten puzzler

In his well-known article ‘Chess Reclaims a Devotee’ (see C.N. 3484) Alfred Kreymborg wrote:

‘In chess, the Rosens bloom on and on. In the old days, over on Second Avenue, the crack players numbered Rosen, Rosenbaum, Rosenfeld, Rosenthal, Rosenzweig – the last truly a twig compared with the others.’

Indeed, there were even two players named H. Rosenfeld – Hector and Herbert – and it is the former who interests us here. His obituary on page 169 of the December 1935 American Chess Bulletinincluded the following:

‘One of the best informed and most respected amateurs in the east, he was brother of the late Sidney Rosenfeld, well-known playwright, who in his day was a familiar figure at the [Manhattan Chess] Club.

Hector Rosenfeld came to New York as a young man from Virginia and was in the manufacturing business until he took up puzzle-making, in which connection he was known as “Hector” for the past 30 years. For a while he was an associate of the junior, Sam Loyd, whose father had a worldwide reputation as “King of Chess Problem Composers”. Mr Rosenfeld was a member of the National Puzzlers’ League and the Riddlers, its New York City branch.’

His obituary on page 24 of the January 1936 Chess Review added the following information:

‘He founded the Riddlers, a New York puzzle club, contributed to Enigma, and was at one time Puzzle Editor of the Ladies’ Home Journal. It is estimated that he composed more than 10,000 puzzles, charades, transposals, anagrams, crosswords, acrostics and other types, which he syndicated through 40 newspapers under the name of “Hector”. Through his interest in puzzles he became acquainted with Sam Loyd and contributed an article about the famous “King of Chess Problem Composers” which was published in our July 1935 issue.’

Many previous C.N. items (see the Factfinder) have discussed the puzzles of Sam Loyd, Hubert Phillips and H.E. Dudeney, and we should like to find out more about Hector Rosenfeld (1857-1935).

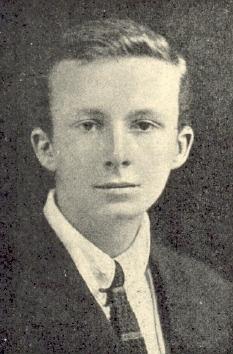

4924. Purdy’s year of birth

In a number of C.N. items (listed on page 271 of Chess Explorations) Cecil Purdy’s year of birth has been discussed. It used to be given as 1907 but now appears in reference books as 1906. In the entry for Purdy in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) one of the citations is the announcement of his birth on page 1 of The Times (London) of 26 May 1906. Below is the text:

‘PURDY – On the 27th March, 1906, at Port Said, to EMILY and J.S. Purdy, M.D., F.R.G.S., Surg.-Capt., New Zealand Militia, a son (CECIL JOHN SEDDON). New Zealand papers, please copy.’

That might be regarded as putting an end to the matter, but, as mentioned in C.N. 1623, page 146 of the 1 July 1949 issue of Purdy’s own magazine, Chess World, stated that he was born, in Port Said, in 1907.

Lest that be thought an isolated erroneous reference, we add that 1907 was given too in an article about Purdy by Gunars Berzzarins on page 282 of the December 1951 Chess World. Also before us lies the second edition of Purdy’s book Guide to Good Chess (Sydney, 1951). Once again, the year stipulated (in a ‘thumbnail biography’ from Who’s Who in Australia) was 1907. Page 161 of the August 1960Chess World had a biographical feature on Purdy, and it too put 1907. Jeremy Gaige was still giving 1907 in the revised edition of A Catalog of Chessplayers & Problemists (Philadelphia, 1971).

However, 1906 was the year presented by Anne Purdy (whom he married in 1934) on page 14 of C.J.S. Purdy His Life, His Games, and His Writings edited by J. Hammond and R. Jamieson (Melbourne, 1982). Assuming that Purdy was not born in 1907, we wonder when exactly he found out.

C.J.S. Purdy in the 1920s (from page 284 of Chess World, December 1951)

| First column | << previous | Archives [32] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright 2007 Edward Winter. All rights reserved.